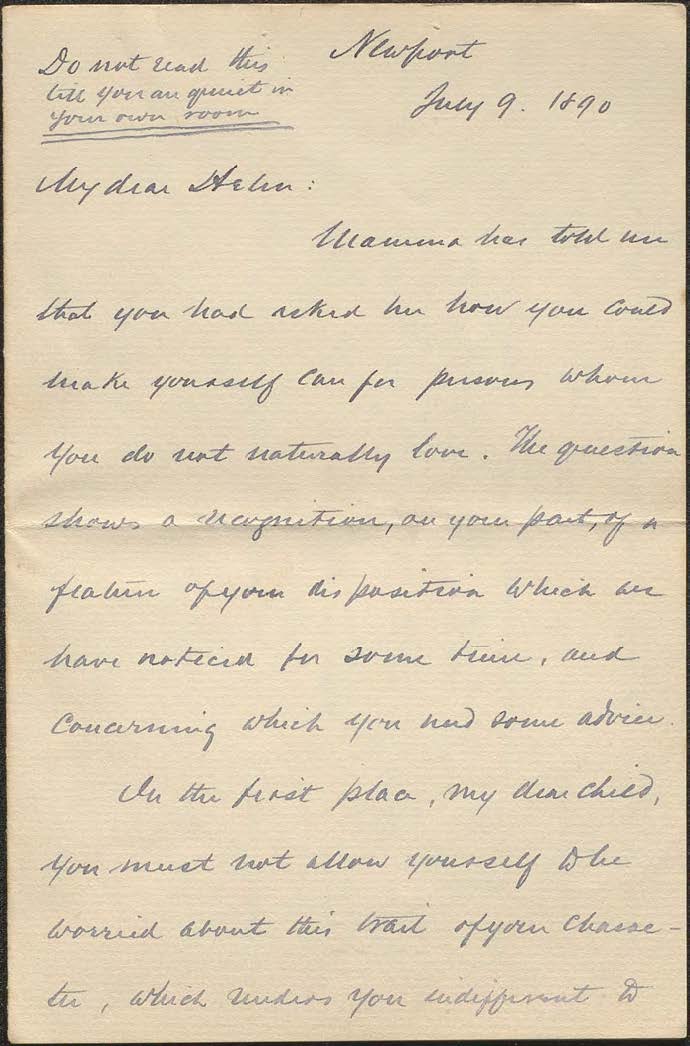

Letter to Helen E. Mahan, 1890 Jul 9

Scope and Contents

Letter written by Alfred T. Mahan to his daughter, Helen E. Mahan in which he provides advice on how to care for people to whom she may feel indifferent towards.

Dates

- Creation: 1890 Jul 9

Creator

Conditions Governing Access

Access is open to all researchers, unless otherwise specified.

Extent

1 item ; 10 pages

Language of Materials

From the Collection: English

Transcription

Newport

July 9. 1890

Do not read this till you are quiet in your own room

My dear Helen:

Mamma has told me that you had asked her how you could make yourself care for persons whom you do not naturally love. The question shows a recognition, on your part, of a feature of your disposition which we have noticed for some time, and concerning which you need some advice.

In the first place, my dear child, you must not allow yourself to be worried about this trait of your character, which renders you indifferent to most persons, as though it were a fault, or a sin, for which you are originally responsible. It was born in you, without your will. But which it is not a fault, it is a very serious defect, against which you are bound as a Christian to strive, as earnestly as you would against any other natural defect, or weakness.

You will notice that indifference to other people, the failure to be moved by their happiness or sorrow, though not as bad as hatred, or ill-will, to them, is nevertheless much opposed to that charity, or love, which our Lord and His apostles dwell upon as the great distinctive grace of the Christian character. It is well to note this. Like yourself, I am naturally indifferent to others; and for many years I thought it almost something to be proud of. I did not muddle with other people’s business, which is undoubtedly a good thing; unfortunately, in me it was due to the fact that I did not care anything about their business, whether it went well or ill. It is only very lately that I have realized that it is not enough to refrain from, and keep under, bad or unkind feelings towards others; charity demands that we have toward them feelings of kindly interest; of sympathy; even of affection, in accordance with the relationship which they bear to us, as relatives, as friends, or as neighbors.

You have in your Aunt Rosie a very good example of what this charity should be – in her affection for her mother. You know how devoted it is. I have heard heard [sic] her say that it is no merit in her to do all she does for her mother because she loves her so; and in that she is quite right, it is no merit in her any more than your indifference is a fault in you; it is a natural trait. But do you not see what a lovely trait it is, and how far better we all would be if we by nature loved others as Rosie loves her mother; not so much, of course, in every case, but having for every one a degree of interest and love proportioned to the relationship to us. That we have not, is because our nature is fallen.

Now as to the means of gaining this better nature, it is necessary to distinguish between your part and God’s part. Your part is to give care and thought as to your loving duty to others, and then to try earnestly and carry it out. First of all in your home; next among your other relatives; then extending to others about you. For instance, at Bar Harbor, there is Grannie and [Marraisse?]. The former can go about but little, and though she has many friends who either from natural affection, or Christian kindness, do to see her, yet every little visit is an incident and a pleasure in her day. I know that she has shown such a very marked partiality for Lyle, that it is not to be wondered at she has lost the affection of her other grandchildren; but the evidence of her love for you is not the measure of your duty of kindness to her. Go to see her frequently, not grudgingly or of necessity; remembering that God loves a cheerful giver. This is less hard than you may think; a moment of prayer and effort of the will, will scatter all sense of inconvenience and reluctance.

But doing this, and such like things, through necessary, will not of themselves give you the spirit of love which you desire. They are external acts, though good acts; and are of the nature of these “works”, of which St Paul says they cannot save us. They are done against our nature, which seeks its own welfare or pleasure rather than that of another person; whereas that which we are to desire is that change of heart, or change of nature, through which we will naturally and without effort do right and kind things. By our present nature we seek self; by our new nature we shall seek the good of others. Her you may see the value of that instance which I have used, of Rosie’s love to her mother. Rosie doubtless dislikes some people, and is indifferent to many; but in one particular she affords a very beautiful example of what our redeemed and new nature will be. She does her kindness to her mother, not because she ought to, but because she loves her by nature; her acts of kindness therefore are not “works,” but “fruits”; they spring naturally from what she is, and therefore, though not meritorious, they are evidence of a character that is this particular is lovely.

Such a change of nature, from indifference to love like this, is beyond a man’s power. Works we can do, but change our nature we cannot. This is God’s part. He requires of us our will and wish, which if we have we will doubtless do works of love; but do what we will, He only can change the heart.

Therefore, to become what you wish, to have kindly interest in and sympathy with others, you must: 1st do works of kindness; and 2d pray continually to God to change your nature in this respect and give you a loving heart. It will take time, but never despair of it. I believe you do try not to have unkind feelings towards others, but don’t stop content with that; aim at having kind interest in them.

Both your mother and I think of you, my dear child, among your present surroundings. Your friends seem to be very kind and fond of you; but we cannot be without some apprehension, believing that they are in their aims and principles entirely worldly – living that is for this world, and not for the next. It is not for me to judge them in this respect, but only to caution you to be careful, and not allow yourself to attach undue importance to, and care too much for, the comforts and pleasures of this world. We are all too apt to do this, but particularly when surrounded by them, as you now are. The “deceits of the world”, as the Litany calls them, are very pleasant, particularly in youth; but the deceit is there, for they are found on experience to be unsatisfying in the end. Yet the strange thing is that even those who have by experience found this hollowness, and even talk of their emptiness, still cling to them by force of habit. I trust you may escape this taking such hold upon you. Remember that life is not only uncertain, but that it is short. You may or may not have a life of average length; but even if you live long – at the longest, life is short; and long before its end pleasure ceases to please. At the end, but one thing gives pleasure; and that is a nature which, having been renewed by God, brings forth those fruits which are pleasant here, love, joy, peace, and which endure beyond the grave.

Lovingly

A.T.M

Subject

- Mahan, Helen Evans, 1873-1963 (Person)

Genre / Form

Repository Details

Part of the Naval War College Archives Repository